Linda Sok

Soft Monument (2019). Images courtesy the artist.

“I try to engage with materials that allow people to access in a way that’s not so confrontational. So I think that’s why I go to materials that are quite soft or beautiful or shiny because it softens the way that people can engage with the trauma that I’m talking about.”

Linda Sok is an Australian-Cambodian artist whose practice predominantly focuses on the materiality of objects and their potentials in relation to her culture. Her experience as a member of the Khmer diaspora informs her investigation of her family’s experience of the Khmer Rouge and their genealogical effects. Stories from her familial and cultural heritage significantly influence her method of representing confrontational notions of trauma and genocide. Linda has exhibited in institutions such as Artspace, Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, Firstdraft Gallery, and SEVENTH Gallery. She graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from UNSW Art & Design with First Class Honours and the University Medal in Fine Arts.

The following conversation took place in July 2020. Linda was in Sydney while Allison was in Adelaide. The second wave of COVID-19 started again in Australia and some parts of Sydney had to go back into lockdown.

Allison Chhorn: Have you been able to work on your art recently?

Linda Sok: I've been trying to. So it was a little bit difficult when I was moving around quite a bit earlier this year. But I've been developing a new way of interacting with Cambodian materials and also connecting with place - so places where I'm staying.

So I've been looking into silk-weaving, which you might know was an art form targeted by the Khmer Rouge. So a lot of the artisans who were practicing silk-weaving were... Well the art form was pretty much erased. So I've been looking back at that practice and thinking of ways I can connect to that practice as an art form and being Cambodian, as a uniquely Cambodian practice as well, in their silk-weaving of the krama [Cambodian scarf] and things like that. And in particular, because my parents and the rest of my family aren't 100% on board with me practicing art. I think it's a way for me to engage with art and Cambodian art as well. So hopefully they can understand that what I'm doing in my art is rooted in Khmer traditions. But yeah, I've been trying to do little experiments, experimenting with different ways of working with that material. At the moment, I've been collecting rainwater that my parents collect in these big buckets around our home and adding salt to them. So you know that – Jrouk Spey [pickled mustard greens]...

AC: Oh, the pickles.

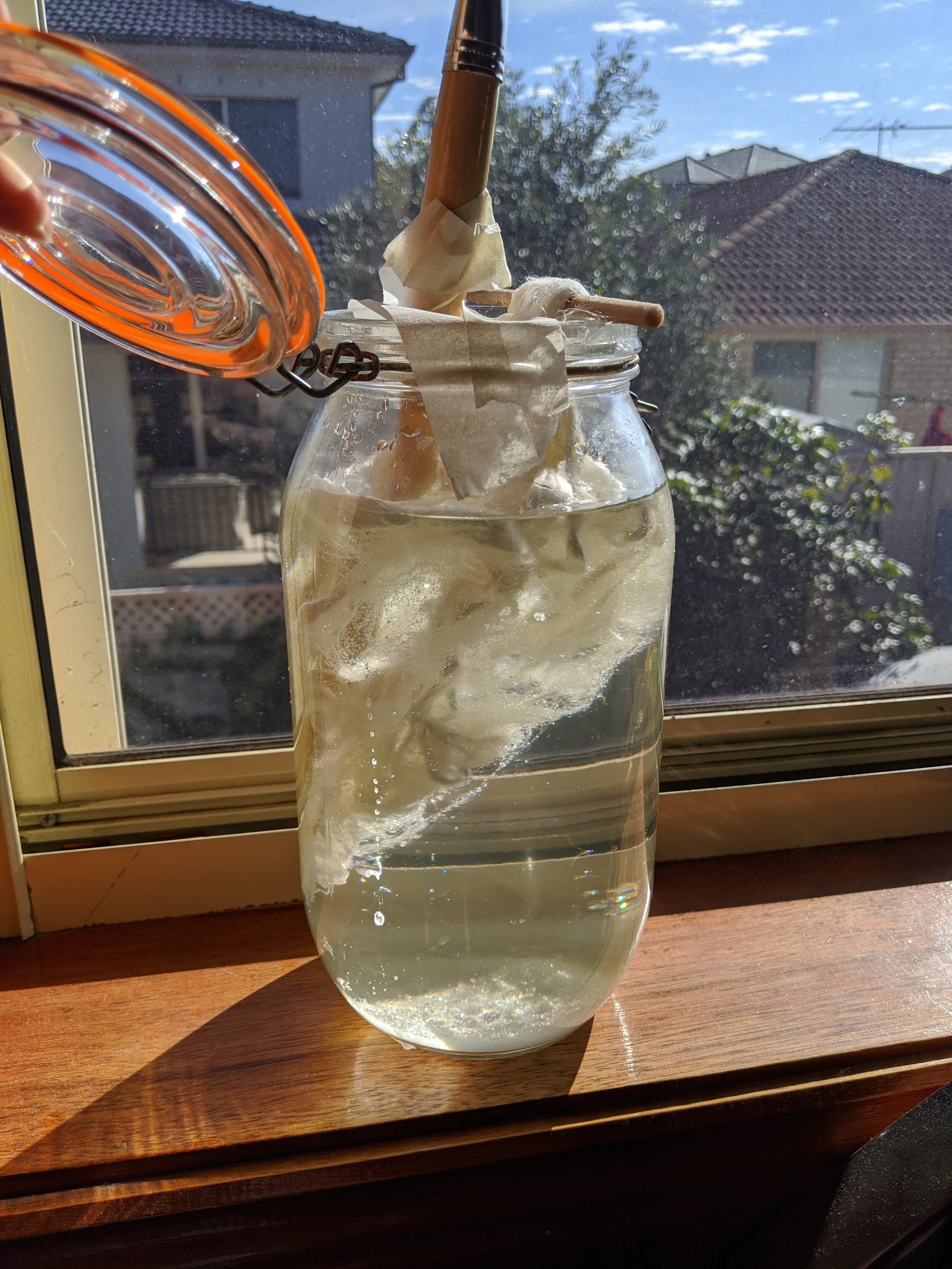

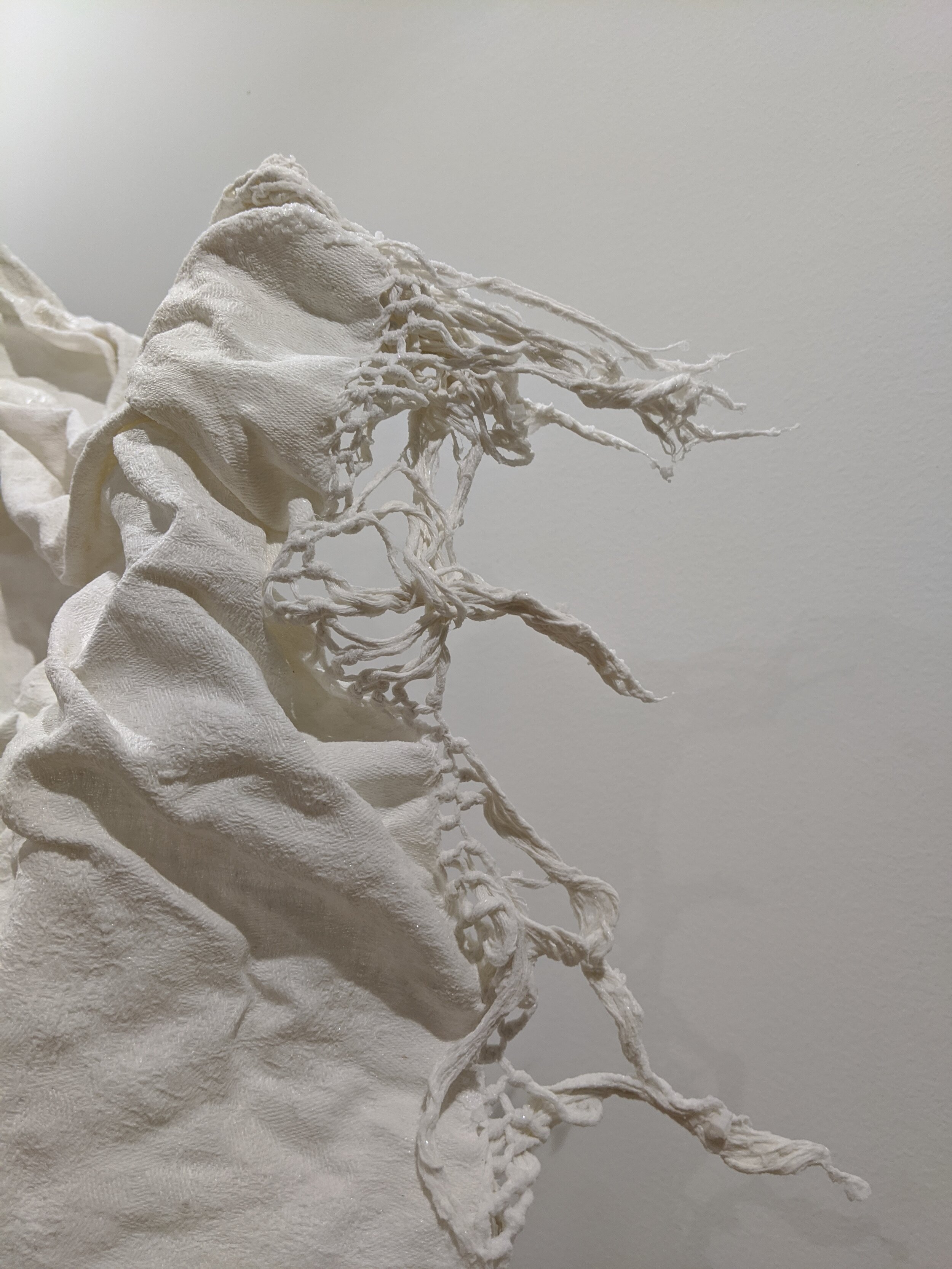

Images from Linda’s instagram

LS: Yeah, so the process of making that has been quite similar to what I've been doing lately. So taking these scarfs and putting them into salt water and putting them into jars and from there it'll crystallise and make these interesting salt textures on silk fabrics. I've been trying to experiment with different types of silks and salt mixtures and just trying to do as many of those little experiments as I can. And that's what I've been doing lately with my practice. Like a little bit of research into the art of silk-weaving as well as engaging with the very practical pickling process. I've also been weaving with silk. So I've just got a delivery of silk and I've been on this little loom that I have. I've just been trying to weave and seeing what that looks like and that process so I can get into that mindset of learning the process of how weaving works. Because I had an idea in my head but not really necessarily, physically how that manifested. So yeah, I've been trying to continue my practice.

It's been weird with COVID. It's sort of allowed me a larger space to sort of work with... Because I think last time I emailed you, I was living away from my parents, but now living at home I'm in a slightly larger space. So that's allowed me to experiment a bit more. I guess COVID's affected me in a weird way; it's both stopped me from making art but also allowed me to make art more in different ways.

AC: Yeah, I kind of feel that as well. Just because of all the news and all the stuff going on, it's hard to kind of find the right energy. But yeah, I agree, it's about trying to find different ways of working. With my work, I'm just trying to find ways to film remotely and if I'm not able to travel, like how am I still able to film and get material?

I wanted to ask about what draws you to specific materials. I feel like it's definitely a part of your family history. Like the rainwater you were talking about, was part of what your family was doing. Why do you think you're drawn to these things?

LS: That's an interesting question. I honestly don't know why I'm drawn to certain materials. I think a lot of it is based on aesthetics. I guess an approach that I've taken with my practice is to - because I work a lot with themes of trauma and the Khmer Rouge – I try to engage with materials that allow people to access in a way that's not so confrontational. So I think that's why I go to materials that are quite soft or beautiful or shiny because it softens the way that people can engage with the trauma that I'm talking about. So often my things are quite beautiful or, the mosquito nets or the gold leaf that I used or joss paper, are quite soft but very tactile. I think there's something about the handmade as well, which quite interests me, where you can see the artist's hand in the making process. So with the joss paper they're often recycled, and with the silk-weaving you can see each of the strands of thread in the material. I think that's what attracts me the most; that embeddedness of a person within the material and it's beauty and it's softness. Also, another thing that I find interesting is things that connect to my Cambodian heritage. Often I use the colour gold because gold is the colour that's quite revered in Buddhist cultures and it's seen as something as precious and important. So I find that using that colour is able to invoke ideas of that preciousness within the histories that I'm speaking about. I guess it's the importance of those histories that I'm speaking about but also that precariousness and the care that has to be taken when talking about them.

For My Ancestors (Ritual for the Dead) (2018-9) & Soft Monument (2019)

AC: Yeah, I think you can really see that in your works “Soft Monument” and “For My Ancestors (Ritual For The Dead)”. Hannah Jenkins, on Running Dog, wrote a really beautiful poem about it. I just want to read a little bit from it that represents what you're talking about: “A soft monument is for when pain is not contained in the single moment, but is present in everyday life in all interactions.”

I feel like it's really difficult to articulate the feeling of generational trauma or the ghostly presence from Khmer history. But I think your work turns that pain into something beautiful.

LS: Yeah, I think that poem definitely captures what I was trying to do in that exhibition [Soft Monument] really well. It's interesting that you brought that up and I'm really glad that you did because I do feel like that it is a really lovely poem. I think a lot of the reasons why I make art in the first place is because I don't feel like I'm the most articulate person. Like I'm not able to engage with my feelings by articulating what I'm feeling necessarily. But I'm able to, well I hope I'm able to, engage with materials in that way and communicate through materials and process. And that then is able to communicate to people my feelings.

--

LS: I think when I was being brought up, I did a lot of Buddhist things, like I would go to the temple, I would celebrate Chinese New Year and Lunar New Year, do Cambodian dance classes and language classes and I don't know if you [Allison] had done any of those things. But it's definitely shaped the way I grew up. I guess Buddhist religion is less strict than other religions and because of that I feel like I've internalised a lot of the Buddhist religion but not necessarily followed it to a tee, you know.

My art practice sort of plays with the idea of ritual as well, but doesn’t necessarily adhere to the Buddhist traditions, but looks at my own way of engaging with those rituals. For example, the work that you mentioned of mine earlier “For My Ancestors (Ritual For The Dead)”, it was about taking the Chinese-Cambodian tradition of burning joss paper and that idea of offering to past ancestors and taking my own interpretation of that by- instead of burning the joss paper- I would take a piece of gold leaf and apply that to a piece of long black fabric in my installation. That was my way of offering and acknowledging my ancestors, I guess, paying respect to them. Even though I don't necessarily believe that there's a reincarnation or an afterlife, there's still that need to respect ancestors. It's like a- I don't know how to describe it- like a warped interpretation of Buddhist ideas and Buddhist logic.

Images from Linda Sok’s Instagram

AC: So you have a lot of documentation of your work on your Instagram page. Is that just part of your process?

LS: Yeah, I think so. I try to post on my Instagram and document my work whenever I remember to. So I think, only quite recently have I tried to really begin posting about the process, as well as the final product. I think the process of doing things is quite interesting as well. It's something that I didn't really do – if you look back quite far I was only really posting final product or exhibition level stuff, not necessarily progress shots. But I think it's been quite interesting to show works that are in progress because it's a nice way of engaging with people, in the way that you're able to engage when you're in the studio space. So once I finished my fine art degree, I didn't have a studio space for a while, and so that ability to engage with people while you're making gets lost. And I found that ability to chat to people while works weren't completed was quite important because you're able to consult with people to say like, “Hey, what do you think of this?” Yeah, not having a studio space really prevented those sorts of conversations from happening. So posting on Instagram was a way for me to try to engage that dialogue with people again. And also show people that I was still making and still doing stuff, even though I wasn't necessarily showing, because I was showing quite often in 2018, and then it kind of slowed down in 2019. Same with this year with COVID, I haven't been able to show at all this year, so I think it was important to continue posting stuff... because everyone was in the same situation, so showing your works in a different way, and continuing to engage with people who were interested is quite important.

“I’d love to engage in a dialogue with [other Cambodian people and especially visual artists] but how do you go about even finding them in the first place?”

AC: Do you know if a lot of young people still go to temples or not really?

LS: I don't think there's very many Cambodian young people who go to the temple, but my parents definitely tried to get me to go when I was younger, which I did.

The last time I went, there was a meeting and they were electing the new group of representatives for a different temple. And I was surprised how political it got as well, you know the kind of tensions between different people, different relationships. But yeah, it was mostly adults that I saw. So I think it's mainly an older generational thing to engage with the community in this way, because that is [the temple] where a lot of the Cambodian community go to connect with people. And I think that's something that's lacking with the younger generation, we don't really have an avenue for connecting and it was great that you reached out to me because now we can have these discussions of what it means to be a 2nd generation descendant of a person who survived the Khmer Rouge. It's hard to find that sense of community anywhere.

I'm also interested to know- do you know of any other Cambodian Artists or people who are working in the creative fields because I feel like - it’s not taboo - but it's a weird space to be in when you're Cambodian because no one really wants you to do art. And I often wonder if it's connected to the Khmer Rouge and how artisans and people who thought differently from everyone else, who were targeted. Yeah, do you know anyone who is working in the creative field who is Cambodian?

AC: Yeah, I've come across a few, just through my research, like the poet Monica Sok. And there are definitely more out there.

I’ve noticed there's a certain time and age with Cambodian artists who are starting to make work about Khmer history and how they feel about it as a younger person that's becoming aware of these things. But I also do agree with what you said about the isolation and not having an avenue to connect.

LS: Yeah, it's definitely something that I've struggled with as well, like thinking about other Cambodian people and especially visual artists. I'd love to engage in a dialogue with them but how do you go about even finding them in the first place? Yeah, it's difficult to know where to find them, but I think it's great that you're connecting with so many different artists. And I think it would end up being a great resource for other Cambodians to hear about their culture and about their history. It's nice that you've fostered this community. I was reading back on the responses I gave to you a while back through email. It was interesting to read about how there were so many commonalities between other Cambodian people. Like you were saying how other Cambodian people feel the same way as I do about that disconnect between themselves and their family. I guess it's nice to have that commonality and connectedness to the community without necessarily having to connect to them, and knowing there are other people out there like me. That's really comforting.